Born in an era of deepening distrust and secrecy amid the Vietnam War, Cold War paranoia and civil unrest, FOIA remains a cornerstone of accountability. But while the federal law opened a window into Washington, every US state has its own version—with its own name, rules, quirks, exemptions and obstacles—offering its own definition of what “public access” means, as shaped by culture, case law and political will. While some throw open the doors, others keep them politely ajar.

If democracy begins with sunlight, it seems many statehouses are still drawing the curtains.

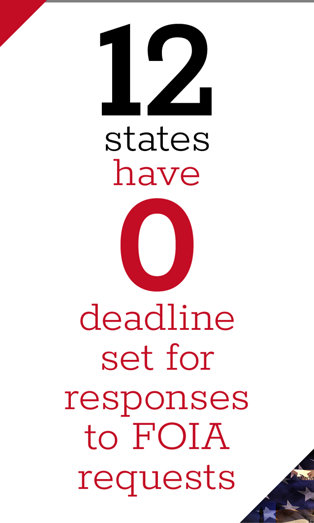

Like the federal FOIA, most state laws contain exemptions—for privacy, active investigations and sometimes security—but they vary wildly in responsiveness. As of April 2023, a dozen states imposed no fixed deadline on the government agency receiving the request, requiring only that it issue a response in a “reasonable” time frame. Among the rest, some mandate action within three days, some within 20.

But while openness is etched into every one of these laws, it often dies in practice—buried under delays, denials and inflated fees.

This guide is your state-by-state road map: how to file a request, challenge a denial, and—when the system stalls—pry it open.

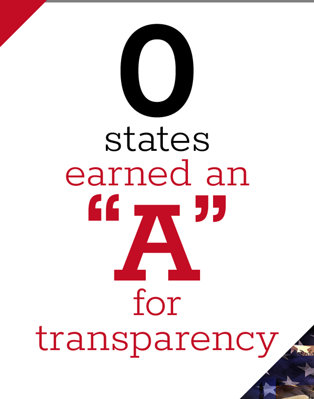

But before the map, a bird’s-eye view of the terrain: A 2015 investigation by the Center for Public Integrity graded all 50 states on transparency across 245 criteria—from lobbying disclosure to access to public records. No state earned an “A.” Just three—Alaska, California and Connecticut—managed a “C,” and that was the highest score. Eleven flunked outright.

So if democracy begins with sunlight, it seems many statehouses are still drawing the curtains.

And yet, the right to know remains one of the few tools citizens can use to confront secrecy, mismanagement and unchecked power.

In a democracy, access to government-held truths is not a privilege—it’s a right. And knowing how to ask and where to knock is more important now than ever.

Recent battles reveal both the fragility of that right and the ferocity with which people will defend it. In Colorado, when lawmakers carved out new secrecy protections for themselves, advocacy groups immediately launched a ballot initiative to repeal the rollback. In New Jersey, a sweeping overhaul of public records law met a wall of public resistance—with civil liberties groups, journalists and 80 percent of surveyed voters pushing back.

If there’s a single lesson in this 50-state odyssey, it’s this: Transparency is not a static achievement—it’s a daily fight. For every loophole or bureaucratic dodge, there’s someone—a reporter, a watchdog, a regular citizen—asking uncomfortable questions and refusing to be ignored.

That stubborn persistence is the true architecture of democracy. And it endures:

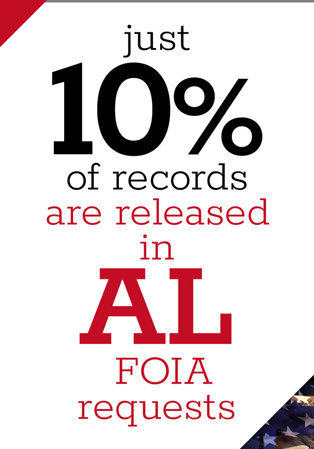

Alabama

Alabama established its open records statute in 1923. But the state ranks dead last in FOIA compliance, with records released in only about 10 percent of requests. A 2024 law introduced response deadlines, but major records like police body cam footage remain inaccessible, and lawsuits are the primary path to enforcement. Learn more here.

Alaska

Alaska passed its public records law in 1900. The law is expansive on paper, yet weak enforcement and slow agency responses too often leave the public in the dark. A 2025 reform bill targets parole board transparency, but access to records remains unreliable. Learn more here.

Arizona

Arizona passed its public records law in 1901. The law’s strength was illustrated in 2024, when litigation forced Cochise County to release thousands of deleted election communications. Learn more here.

Arkansas

Arkansas passed its public records law in 1967. The state restricts records access to in-state residents. A 2023 law signed by Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders further narrowed transparency by shielding her travel records. With no independent enforcement agency, residents must sue for access. Learn more here.

California

California passed its public records law in 1968. The state offers strong public access, but chronic delays, privacy exemptions, and the rise of records-related lawsuits have eroded the law’s effectiveness. Agencies rarely face consequences unless taken to court. Learn more here.

Colorado

Colorado passed its public records law in 1969. But transparency took a hit in 2024 when lawmakers passed a bill exempting themselves from open meetings law. A repeal effort and 2026 ballot initiative are underway. High fees and lack of enforcement add further barriers. Learn more here.

Connecticut

Connecticut passed its public records law in 1975. The law mandates prompt acknowledgment of FOIA requests, but agencies often respond with auto-replies and then disappear. No deadlines for request fulfillment and minimal accountability have made delays the norm. Learn more here.

Delaware

Delaware passed its public records law in 1977. Access is restricted to state residents and the law has long been criticized for shielding lawmakers’ emails and lacking meaningful oversight. Reform advocates argue the law hasn’t evolved since the 1970s. Learn more here.

Florida

Florida passed its Sunshine Law in 1967. The state once set the national standard with its Sunshine Law, but over 1,100 exemptions—many citing privacy or security—have chipped away at its openness. Transparency advocates warn of steady legislative erosion. Learn more here.

Georgia

Georgia passed its public records law in 1959. The law requires agencies to respond within three business days, but the General Assembly exempts itself from disclosure, limiting insight into lobbying and legislative negotiations. Learn more here.

Hawaii

Hawaii passed its public records law in 1975. The Uniform Information Practices Act contains broad privacy exemptions and few teeth for enforcement. Learn more here.

Idaho

Idaho passed its public records law in 1990. The law is hobbled by 92 exemptions, significant fees and the absence of an ombudsman. Legal action is usually required to force compliance. Learn more here.

Illinois

Illinois passed its public records law in 1984. Its framework is robust in theory, but exemptions like “unduly burdensome” are routinely abused to avoid compliance, especially when requests target corporate–government collusion. Learn more here.

Indiana

Indiana passed its public records law in 1983. It allows long delays because it lacks any deadline to fulfill requests—just a vague requirement for “reasonable” timing. In 2024, lawmakers curtailed the powers of the state’s transparency watchdog, sparking backlash. Learn more here.

Iowa

Iowa passed its public records law in 1967. The state’s courts recently ruled that ignoring a freedom of information request is tantamount to denial. Yet enforcement remains weak, and some lawmakers have floated measures to let agencies blacklist “vexatious” requesters. Learn more here.

Kansas

Kansas passed its public records law in 1984. Transparency suffers from numerous, largely outdated exemptions and a lack of enforcement. Modest justice reforms haven’t yet translated into progress. Learn more here.

Kentucky

Kentucky passed its public records law in 1976. The state still faces delays and high fees for public records access. With no enforcement agency, individuals must appeal to the attorney general or sue. Learn more here.

Louisiana

Louisiana passed its public records law in 1940. The law is weakened by excessive exemptions and minimal enforcement. Citizens are often billed thousands for records. Learn more here.

Maine

Maine passed its public records law in 1959. The state leads in election transparency through ranked-choice voting, but access to public records is slow and often unresolved unless the requester sues. The state’s ombudsman has no enforcement authority. Learn more here.

Maryland

Maryland passed its public records law in 1970. The state overhauled its police oversight laws in 2021, but enforcement of FOIA remains weak. Disputes can be mediated but not compelled, leaving access to public records uneven. Learn more here.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts passed its public records law in 1973. The state is uniquely opaque: All three branches of government are exempt from its public records law. Requesters are directed to submit their inquiries to the governor’s office, omitting any mention of its public records law exemption. The office provides its own request form and has a designated records access officer to handle submissions. Learn more here.

Michigan

Michigan passed its public records law in 1977. The state has exempted both the governor and legislature—an issue reformers are trying to fix through pending legislation. Learn more here.

Minnesota

Minnesota passed its public records law in 1974. The state offers public access in theory, but practical enforcement is slow, expensive and often prohibitively bureaucratic. Formal complaints can cost $1,000, deterring many from seeking redress. Learn more here.

Mississippi

Mississippi passed its public records law in 1983. The state has failed to enforce its deadlines, allowing delays that stretch hundreds of days. A 2025 court ruling excluded the legislature from the open meetings law, undermining public trust further. Learn more here.

Missouri

Missouri passed its public records law in 1973. The state’s law is relatively strong, but enforcement suffers from the attorney general’s 2021 refusal to enforce it against the governor’s office, citing an “attorney–client” relationship. The move raised alarms, effectively placing the governor above public records scrutiny and leaving Missourians with little recourse. Learn more here.

Montana

Montana passed its public records law in 1972. The state enshrines the right to public access in its constitution, but has no ombudsman or enforcement mechanism. Residents must sue to enforce access. Learn more here.

Nebraska

Nebraska passed its public records law in 1961. The state promises fast response times but allows agencies to charge high fees. A 2024 court ruling upheld a $44,000 fee for environmental records, drawing criticism from watchdogs. Learn more here.

Nevada

Nevada passed its public records law in 1911. The law is strong on paper, but agencies frequently deny access. A proposed ombudsman could help mediate disputes, though experts question whether it would have enforcement power. Learn more here.

New Hampshire

New Hampshire passed its public records law in 1967. The state’s Right-to-Know Law has produced real wins for accountability but still suffers from bureaucratic delay. Despite the state’s high rankings for freedom at large, freedom of information access can be a slow, frustrating process. Learn more here.

New Jersey

New Jersey passed its public records law in 1963. Courts clarified that non-residents can use the state’s Open Public Records Act, but recent legislative changes have raised fears that access could shrink. Transparency advocates are sounding the alarm. Learn more here.

New Mexico

New Mexico passed its public records law in 1947. Requesters can sue immediately after a denial, with no need to exhaust appeals. The state’s Inspection of Public Records Act and the Open Meetings Act both provide strong protections—but enforcement is inconsistent, and a recent legislative effort seeks to place new limits both on what constitutes public information and who can access it. Learn more here.

New York

New York passed its Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) in 1977, but the state suffers from systemic failures in its fulfillment of requests. More than 70 percent of towns in New York do not post meeting documents online, and nearly 40 percent of counties fail to acknowledge requests within five business days, as required by law. A backlog in New York City left 16 percent of 2024 FOIL requests still pending after a year. Learn more here.

North Carolina

North Carolina passed its public records law in 1935. The state has strong laws, but public access is hampered by inordinate delays, stiff fees and a contentious 2023 law that empowers lawmakers to decide which—if any—public records to disclose. Most violations must be challenged in court. A 2021 law created a publicly accessible misconduct database for police—a step forward for FOIA-based transparency—but broader reforms lag. Learn more here.

North Dakota

North Dakota passed its public records law in 1957. The state allows citizens to request attorney general opinions on violations of records disclosures by official custodians. Record-sealing laws allow certain criminal histories to be hidden after a waiting period. Learn more here.

Ohio

Ohio passed its public records law in 1963. Requesters—not just from the state but from anywhere—are required to fill out a form and wait three days before filing complaints in court. A 2024 law allows agencies to charge up to $750 per video to redact body cam footage—with the bill passed to the requester, effectively pricing many members of the public out of access. Learn more here.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma passed its public records law in 1959. The state’s Open Records Act has many exemptions and no ombudsman. Agencies can ignore requests unless sued. A 2025 lawsuit forced a police department to admit it had wrongfully withheld records. Learn more here.

Oregon

Oregon passed its public records law in 1973. The state has an extensive list of layered exemptions that confuse requesters. Disputes can be mediated by petitioning the attorney general or local district attorneys, but enforcement power is lacking. Lawsuits remain the ultimate means of redress. Learn more here.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania passed its public records law in 1957. The Right-to-Know Law offers a formal appeal process through the Office of Open Records, but the state’s Sunshine Act governing meetings must be enforced in court. Police hiring transparency remains spotty despite reforms. Learn more here.

Rhode Island

Rhode Island passed its public records law in 1979. The state empowers its attorney general to investigate and enforce public records access, and recent upgrades to training and public tools aim to improve compliance. Agencies found to have knowingly and willfully violated the law may face fines up to $2,000, while reckless violations can result in fines up to $1,000. Learn more here.

South Carolina

South Carolina passed its public records law in 1974. The state reformed its law in 2017 to lower fees, speed up responses, and grant individuals the right to request and receive electronically a public record if it exists digitally. But enforcement still requires court action, as the attorney general neither enforces open government laws nor handles complaints directly. Learn more here.

South Dakota

South Dakota passed its public records law in 1939. The state allows reduced fees or outright waivers for public interest requests and encourages transparency, but enforcement is limited and still maturing after a 2009 legal overhaul. Learn more here.

Tennessee

Tennessee passed its public records law in 1957. The right to access public records is generally reserved for the state’s citizens, but government agencies have the discretion to grant access to non-citizens. Tennessee offers advisory opinions through its Open Records Counsel, which is authorized to informally mediate and assist with the resolution of disputes but has no real enforcement. A 2025 report revealed massive data gaps and delays in the court system of Shelby, the state’s most populous county, which has long grappled with criminal justice backlogs and racial disparities. Learn more here.

Texas

Texas passed its public records law in 1973. The Public Information Act grants strong rights—and there are efforts underway to expand its scope beyond public records to private nonprofit associations that represent or do business with government entities. But agencies can stall by requesting attorney general rulings. Recent legislation has focused on bail reform, which, like other police oversight reforms, often hinges on changes to transparency laws. Learn more here.

Utah

Utah passed its public records law in 1991. The state’s Government Records Access and Management Act includes deadlines and an appeals board, but enforcement ultimately depends on courts. In 2025, a series of efforts under the guise of transparency “reform” weakened the law’s reach and were strongly opposed by the state’s legal community. By stripping away the citizen-led records appeals panel in favor of a governor-appointed reviewer and restricting legal fee recovery, paths to accountability were effectively narrowed. Learn more here.

Vermont

Vermont passed its public records law in 1975. The state promises fast FOIA turnarounds but offers no dispute resolution body. Citizens must sue. Learn more here.

Virginia

Virginia passed its public records law in 1976. The law is restricted to state residents and in-state media. The US Supreme Court upheld the policy in 2013 after it was challenged by two out-of-state requesters. The Virginia Freedom of Information Advisory Council provides guidance but neither mediation nor enforcement. Learn more here.

Washington

Washington passed its public records law in 1972. The state’s Public Records Act is robust but under strain. Response times are lengthening, and lawmakers increasingly invoke “legislative privilege” to avoid disclosure, thereby eroding the act’s effectiveness. Learn more here.

West Virginia

West Virginia passed its public records law in 1977. The state’s Freedom of Information and Open Governmental Proceedings Acts do not require public agencies to create new records—only to provide access to records that already exist and are in their possession. However, under state common law, public officials are expected to create and maintain records related to their official duties. In April 2025, lawmakers broadened their overhaul of the state’s Freedom of Information Act, excluding some legislative records from public disclosure, thereby further weakening the public’s right to know. Learn more here.

Wisconsin

Wisconsin passed its public records law in 1981. The state enforces open government laws primarily through courts. Transparency advocates have called for state agencies to post request logs, improve response tracking to bolster public trust, and make it easier for requesters to recover attorney fees when a government entity does not release records. Learn more here.

Wyoming

Wyoming passed its public records law in 1969. The state has a 30-day response time for FOIA requests under its Public Records Act, plus a mediation-oriented ombudsman, but final enforcement generally requires litigation. Learn more here.

A fierce and relentless advocate of FOIA from its inception, the Church of Scientology was acknowledged by former director of the US Justice Department’s Office of Privacy and Information Appeals, Quinlan J. Shea Jr., for its work endeavoring “to shine more light on government.” The Church’s long and proud history of taking to task government agencies attempting to withhold information from the public is inspired by these words from Scientology Founder L. Ron Hubbard: “Democracy depends exclusively on the informedness of the individual citizen.”