And for over a century, the BBC has been as much a part of British culture as tea and crumpets.

The world’s oldest and largest broadcast news-gathering operation, the BBC has long wielded enormous influence across the UK and the Commonwealth. For generations, crowned heads used it to speak to their subjects, and ordinary citizens relied on it as their eyes and ears on the great and small events of the day.

But over the last two decades, it has begun tripping over its own feet with increasing regularity.

“It’s now become a laughingstock, and it needs to be put out of its misery.”

The latest face plant, in which the BBC made the news instead of reporting on it, was its doctoring of a speech delivered by the US president on January 6, 2021. The speech was drastically changed, with editors splicing together two sentences—one delivered nearly an hour after the other—producing a wildly out-of-context “quote.”

Airing on the BBC’s documentary program Panorama (the UK’s equivalent of 60 Minutes), the bogus speech was viewed by millions.

The scandal led one media critic to state that the BBC had “thrown impartiality to the wind,” and prompted former UK parliamentarian Liz Truss to declare: “They’ve lied, they’ve cheated, they’ve fiddled with footage.”

“The BBC used to be the paragon of journalism across the world,” she added. “It was respected. It’s now become a laughingstock, and it needs to be put out of its misery.”

The BBC, a national institution created by royal charter and authorized by the British government, is supported by an annual fee of £174.50 ($230)—paid by every British household with a TV set. It’s the Commonwealth’s Big Dog as far as the relay of news is concerned, and it operates under a charter that demands impartiality, transparency, accountability and service to the public interest.

But the recent scandal, which toppled two executives this month—Director-General Tim Davie and News CEO Deborah Turness—is just the latest in a long series of BBC catastrophes.

Last month, Britain’s media regulator characterized the broadcaster’s documentary on the lives of children in the Middle East as “materially misleading” for failing to disclose that the father of the teen narrator was a leader in a terrorist organization closely connected to that war-torn zone.

Four months prior, the BBC was condemned for livestreaming a rap punk duo who urged a crowd at the Glastonbury Festival to chant “death” toward the military of a British ally. This time, it was the BBC’s complaints unit that found the broadcast violated editorial guidelines. Director-General Davie apologized and regretted that “such offensive and deplorable behavior” was aired.

But aired it was. And the scandal didn’t end—or begin—there. Under Davie’s leadership, July 2023 brought the revelation that his highest-paid news anchor had purchased sexually explicit photos of a teen. While Davie suspended the anchor, he yet continued to enjoy a lush salary, and later pleaded guilty to possessing images of child sexual abuse.

In 2012, when it was discovered that one of the BBC’s most popular broadcasters had been a serial sexual abuser of young women before his 2011 death, the network buried the story. George Entwistle, BBC’s Director-General at the time, was forced to resign over the atrocious cover-up.

Taken together, these scandals reveal more than isolated errors—they point to systemic failures within the world’s oldest and largest broadcast news-gathering operation. And that institutional rot extends even into its reporting on religion, where bias and bigotry have long been nurtured and condoned.

In the spring of 2012, for example, a BBC documentary on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints leaned heavily on hostile canards attacking the religion. The program was described by one writer as “a hatchet job,” while another described it as employing “gotcha-style reporting” that included “detailed interviews with disaffected Latter-day Saints who seemed willing to mock things I hold sacred.”

Sweeney erupted in rage at a Church spokesperson in an on-camera tirade that swiftly went viral.

The individual the BBC entrusted to cover people of faith was one John Sweeney, a reporter with a reputation for not letting the truth get in the way of a juicy story. The ultimate poster child for the devolution of the BBC, his professional procedure bears no resemblance to his purported trade: “There are three rules in journalism,” he explained. “First, find a crocodile. Two, poke it in the eye with a stick. Three, stand back and report what happens next.”

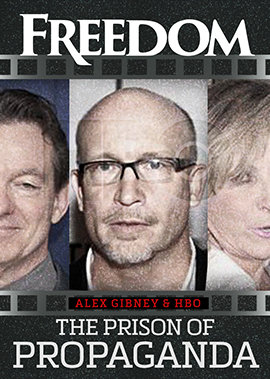

In 2007, BBC gave Sweeney license to organize an anti-religious hit piece on the Church of Scientology—one that relied on two former Scientologists who had attempted to extort money from the Church. Sweeney, who even admitted that “annoying the Church of Scientology” was a “hobby” of his (how journalistic!), pursued that hobby with gusto, abandoning any shred of objectivity in favor of naked hate.

During the production, he could no longer contain his animus; Sweeney erupted in rage at a Church spokesperson in an on-camera tirade that swiftly went viral, earning him the moniker “the exploding tomato.” The incident has since been used in journalism classes as a perfect example of how not to conduct an interview.

A UK university ethics review identified 180 violations of BBC guidelines and national broadcasting regulations in Sweeney’s anti-Scientology “coverage.”

How did the BBC deal with this shameful episode, in which its “reporter” humiliated himself, his network and his profession before the entire world?

Did it dismiss Sweeney as a disgrace?

Did it suspend him, sending him back to Journalism 101?

Did it demote him, at the very least?

No. The BBC commissioned him to do a second “documentary” on the Church in 2010—just as bigoted and trashy as the first.

Nine years later, the BBC finally dumped Sweeney, but only after he was caught on film making racist and homophobic remarks while plying a young woman with drinks—on the BBC’s tab—in an attempt to get her to dish on her ex-boss, a politician he sought to smear.

“It feels like it’s the end for me,” he moaned.

Meanwhile, the BBC remained calm and carried on with its biased reportage, even after parting ways with Sweeney.

All of which begs the question: Why has an institution once chartered—and revered—for openness, transparency and accountability fallen so far?

Veteran BBC correspondent Robin Aitken offered a revealing answer. “The problem is that holding the BBC itself to account is very difficult,” he said. “The BBC conducts and orchestrates the court of public opinion, and it is the BBC which often holds organizations and individuals to account when there has been wrongdoing.

“Now, if the BBC itself is guilty of transgressing its own obligations to fair play and balance, then who holds it to account? One might think politicians can hold the BBC to account because Parliament is sovereign, but politicians are afraid of the BBC—and with good reason. Any politician who wants to make headway in Britain has to make sure they’ve got the BBC on side. If you’re not, then you’re going to get a bad press.”

With confidence in journalism at historic lows, the BBC cannot afford further missteps—it must clean house, enforce accountability and resurrect the credibility it has eroded so recklessly.

Otherwise, as scandals, resignations, ethical breaches and institutional arrogance continue to mount—all on the taxpayer’s dime—the day nears when the BBC may find itself kicked to the curb, muttering, just like its disgraced ex-reporter, “It feels like it’s the end for me.”