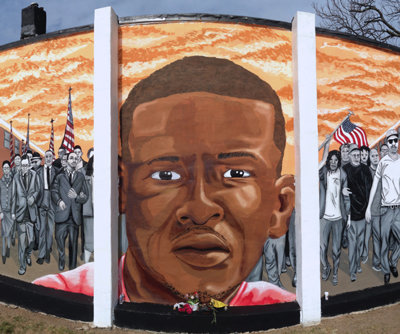

There was nothing about Freddie Gray that was considered particularly remarkable before his life was cut woefully short at 25 this past spring. The lifelong Baltimore resident had two sisters (one of them his twin), with whom he was living in the destitute Sandtown-Winchester area. He was reportedly unemployed at the time of his death—like roughly half of the adults in the neighborhood. He carried a sizable criminal record, mostly for drug charges and petty crimes, and served time for narcotics possession.

Gray was just your average inner-city cautionary tale in progress, a young African-American male well on his way to amounting to little, a bleak product of a bleaker environment.

But then fate intervened.

Arrested for possession of an illegal switchblade on April 12, Gray suffered a fatal spinal cord injury while in police custody—shackled but unrestrained and allegedly tossed around like a rag doll during transport in the back of a police van. He died April 19, sparking a wave of disruption and dissent that entangled Baltimore in violent protests and civil unrest for two tumultuous weeks, marked by heated demonstrations and wall-to-wall news coverage.

The uprising culminated May 1 when Baltimore City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby filed criminal charges against the six officers involved in Gray’s arrest and subsequent death (ruled a homicide by a medical examiner), including for second-degree murder and manslaughter. Three of those officers are black.

A formal grand jury indictment on similar charges followed 20 days later.

On the heels of the initial criminal charges, tension in the city quickly evaporated, even though the systemic racism in Baltimore that helped ignite the powder keg in the first place remained utterly unchanged.

While it seems clear that the life of Freddie Carlos Gray Jr. may rightly be perceived as a tragic waste—and his death that of a martyr—it may prove to be anything but in vain.

However, several questions remain. Chiefly: Where does Baltimore go from here? What connection, if any, did the uprising have to the turmoil last summer in Ferguson, Missouri, that followed the police killing of unarmed teenager Michael Brown? Are we witnessing the roots of a genuine social justice movement? And what role is the faith community playing in uniting and helping to heal a shattered region?

There are, perhaps, no easy answers. But the single area of agreement among clergy, community leaders, activists and educators is that the culture of minorities (both black and brown) feeling disenfranchised, marginalized, despairing, voiceless, profiled and targeted must change or there will be innumerable Fergusons and Baltimores in America’s future.

“This is about getting justice in America,” stresses DeRay Mckesson, a former school administrator who has used social media and a newsletter called This Is the Movement to galvanize interest. “The police shouldn’t be killing people, and it shouldn’t take this much energy to get them to stop,” he says.

Mckesson maintains that what he is fighting for is simple: “A world where you shouldn’t be afraid of the people who are supposed to protect and serve.”

Certainly, the movement has taken flight in specific response to law enforcement’s killing of unarmed black men, dating to the February 2012 death of teen Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, at the hands of George Zimmerman (who was not a cop but a neighborhood watch volunteer); the July 2014 death of Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, after being placed in a police chokehold; Michael Brown’s shooting death by a police officer in August 2014 in Ferguson; then, in quick succession, the killings of Freddie Gray and Walter Scott, shot repeatedly in the back by an officer while fleeing, in North Charleston, South Carolina.

Besides their lack of weapons and the color of the victims’ skin, what most of these cases share is the presence of cell phone video (documenting three of the killings) and the use of online social media to trigger and sustain interest—provoking protests on a far wider scale than the country had seen before.

No longer is the revolution only being televised. It is also being tweeted by smartphone soldiers such as Mckesson to his 125,000 followers—vowing to continue the fight “until we consistently both see justice for those who are targeted in the trauma and accountability for those who perpetrate it.”

Like the civil rights and antiwar movements of the 1960s, the present activism is spearheaded by young people. Mckesson is just 29. And in the cases of both Baltimore and Ferguson, the catalyst driving the demand for reform is infinitely more complex than a single incident.

Perhaps at the source of it is the vast disparity between the haves and the have-nots—which in Baltimore means a privileged white class and an African-American underclass in a town that’s 62 percent black, much of it subsisting below the poverty line.

Frederick Opie, a history professor at Babson College in Wellesley, Massachusetts, and author of the book Upsetting the Apple Cart that looks back at black-Latino coalitions in New York City from the 1960s thru the ‘80s, believes Baltimore’s deep racial divide is no accident.

“Behind the uprising in Baltimore, Ferguson and other cities, there has been a systematic and successful attempt to keep African-Americans out of certain neighborhoods, marginalized and locked into ghettos,” he said.

“We’re talking about charging people exorbitant prices for inferior housing, medicine and food, and trapping them in a situation where there’s no escape. If you not only neglect a community but then on top of that take away their hope, it’s eventually going to explode. That’s what happened in Baltimore.”

Television networks—CNN, Fox News, MSNBC—raced into Baltimore in late April only after some of the protests had deteriorated into riots and looting, to capture the sensationalist spectacle. What they appeared to have less interest in covering was the overwhelming majority of demonstrators marching and protesting peacefully—and even forming a human line to protect police from instigators and rowdies.

Indeed, the TV cameras were drawn to where the action was in Baltimore, even if that action was hardly indicative of the protests’ true nature. Night after night, they captured the chaos of a few dozen agitators hurling rocks, burning patrol cars and busting into stores to loot whatever their arms could carry—including targeted break-ins of pharmacies to cart away drugs.

A few blocks away, while some 10,000 boisterous but lawful citizens marched for peace—peacefully—the mainstream media’s lenses were conspicuously missing. The squeakiest wheel got the grease, and the attention.

“You had thousands of good, law-abiding people participating peacefully,” said Bishop Keith Allen, senior pastor at Rehoboth Church of God in Baltimore. “That was one of the positive things to come out of this situation.” There was “maybe 1 percent creating mayhem.”

That those same good people are among members of the black community unfairly and disproportionately targeted by law enforcement for harassment and brutality is “one of the things that has to change,” Bishop Allen said. “The police department must reform its strategy in dealing with a black community filled with poverty and unemployment, and with a lack of sound education and good nutrition for its children.”

In early May, in response to the unrest in Baltimore and its spread to nearby Washington, D.C., the Church of Scientology joined in a multifaith meeting involving some 100 clergy and private citizens to vow solidarity in working toward nonviolent protest solutions.

Grassroots efforts continue going forward to bring Baltimore back together, by Bishop Allen and many others including the Rev. Michael Parker, a 31-year-old pastor of the United Methodist Church in Baltimore who graduated from seminary only in May. Parker grew up next door to Freddie Gray and his family, playing with Freddie and the Gray children as a youngster. It has made the situation for him, perhaps, even more fraught with emotion.

“Now that CNN and MSNBC are gone,” Rev. Parker said, “it’s left to us to deal with, and try to make some sense out of, everything that has transpired.”

Rebuilding the trust between Baltimore residents and the city where they reside is a big part of that, Parker believes. It concerned him that even his own church wasn’t calling the community together in prayer in the wake of Gray’s death and the subsequent unrest. So he did it himself. That included sitting down in his sanctuary with 20 gang members to talk, pray and together find light at the end of what was a very dark tunnel.

“Faith leaders need to carry a very active role in this situation,” Rev. Parker insisted. “It’s simply not an option to remain silent and not speak truth to power. In times of trouble, people still look to the church. We need to be a tangible hands-on source of relief and assistance to the communities where we sit and worship.”

Part of the difficulty in organizing the current movement is the lack of a respected, charismatic leader to carry the torch, Bishop Allen noted. “We need someone who can drive reform and unite the different factions as the Rev. Martin Luther King did in the 1960s. A figure like that comes along once every generation. But this is, after all, a new generation.”

Where there remains plenty of unity is in the widespread belief that racial profiling and abuse by police is a driver of much of the rancor. This is typified by the response of Mckesson when asked how long and sustained he believes the protests will remain in the aftermath of Baltimore.

“The police haven’t stopped killing people,” he offered, “and because they haven’t stopped killing people, people haven’t stopped protesting. I think people will protest as long as that continues.”

Of course, the occasional need to use lethal force has always gone along with the dangerous job of being a cop. The issue surrounds the key word “need”—and the role that ethnicity might play in that equation.

After a notorious and deadly May 16 shootout at the Twin Peaks restaurant in Waco, Texas, reportedly involving brawling white bikers, there was initial skepticism as to why the media posted photographs of the motorcycle gang members calmly sitting on the curb outside the eatery while police milled about.

Mckesson pointed out, “When there is the threat of black people assembling, it quickly grows to become a literal state of emergency. It’s different when white people do it.”

But to demonstrate that law enforcement doesn’t always discriminate according to race, there were early reports that police may have fired indiscriminately into the biker crowd. It was alleged that all nine of those killed were shot by police officers rather than each other, as were all 18 of those injured. The situation remained under investigation at press time, and the 177 participants/witnesses arrested were being held on million-dollar bonds.

It all leaves the perception with some that police officers have become an enemy to be feared rather than society’s civilizing protectors. More than anything, especially in minority neighborhoods, the police are seen operating with something resembling rogue impunity.

There are those, however, who do not agree that it’s that simple. Among them is Professor Opie, who said he wonders if we should be looking at the politicians who got elected on tough-on-crime initiatives—and then put pressure on sergeants and lieutenants to carry them out—rather than indicting police officers tasked with fulfilling them.

“I really do feel for the police officers,” Opie said, “because one or two bad apples in a precinct really messes up everybody. And we’re asking these people to go into a hostile environment. They’re forced to maintain law and order in communities consumed with anger and poised to explode, when it was the federal and state government and years of neglect and systemic marginalization that fueled the fire.”

The professor said he also wonders, in the case of Freddie Gray, which of the six Baltimore officers charged in his death was directly involved and which may have been bullied and intimidated into going along with it.

Adding a decidedly blunt voice to the debate is Jonathan Farley, a controversial professor at the predominantly black Morgan State University in Baltimore, who believes the African-American community has only itself to blame for its heavy policing and perceived law enforcement persecution.

“If African-Americans don’t want negative interactions with the police,” he stressed, “they should clean up their own house. Much of the crime in Baltimore can’t be solely blamed on the lack of jobs. There are poor people in Ethiopia and you don’t see the same crime rate.”

Farley pins much of the problem on households run by single mothers and children raised without values—or fathers.

“The riots are not the beginning of a new civil rights movement,” Farley believes, “but they portend the end of white America’s patience with black Americans blaming their problems on racism.”

Eddie Conway sees things far differently. A former member of the revolutionary Black Panther Party founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in 1966, he served nearly 44 years in the Maryland prison system for a crime he says he didn’t commit. He says he was incarcerated as a political prisoner and framed by the infamous FBI Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO).

Yet Conway harbors no bitterness and has, in fact, become a force for positive change since his release in March 2014, speaking at colleges and universities and working as a community organizer for the Quaker peace and justice-striving American Friends Service Committee.

Conway finds many differences in America today compared to 1971 when he went to prison. And it’s not just computers, cell phones and the Internet.

“Unfortunately, the conditions I’m seeing in Baltimore are far worse than those when I went in,” Conway observes. “It’s a tale of two cities, really. Some segments of the community have made great advancements, but the majority is steeped in poverty that’s significantly more severe than 40 years ago.”

One doesn’t need to have been incarcerated for the whole of his adult life to be struck by an overwhelming sense of déjà vu in all of this. History is repeating itself in the fight for African-Americans to overcome a stacked deck and navigate a path strewn with pitfalls, taking their turns at bat with two strikes already against them.

Too, in the current protest wave, there appears to be a kind of inevitability at work. This is the view of Steven Radil,

“We’ve noted a 50 percent increase in the total number of protests around the world since 2006,” Radil said, “which is unprecedented since the late 1960s. And interestingly it’s in the places where we’ve seen the most progress in the human condition, where we find the largest emergence of discontent as well. If we’re going to paint with a really broad brush, it could well be simply about justice.”

Justice—or the lack of it—surely appeared to be at the heart of what spurred the eruption in Baltimore. Ex-Panther Conway calls it at once “disheartening and encouraging” to see young people finally stand up and say “Enough!” to what they perceived as an unconscionable wrong. And he said he believes that same dynamic is poised to be repeated in cities across the country, all of which would be wise to gear up in anticipation.

“It’s a movement as surely as civil rights was a movement in the ’60s,” Conway emphasized. “This is about young America taking back control of their country. It’s about the relationship of young people—and the older people who support them—to their future, to jobs, to the health of the planet, and to the culture.”

Why would a man who was a member of the Black Panthers—a group notorious for standing up and fighting for African-American rights by any means necessary, violent or otherwise—suddenly embrace peaceful dissent?

“The Panthers were all about peace, too,” insisted Conway. “We just felt that in order to have peaceful protest, we needed to protect ourselves at the same time from those who aimed to abuse and dehumanize us, to attack and shotgun and bomb us. But this is a different time. We didn’t have social media back then.”

Today, opportunity is nonetheless at hand to rouse something transformative and sustained, to coalesce the grassroots power of people collectively frustrated by injustice and inequality.

“There is a feeling in the air, after Ferguson and Baltimore, that we suddenly control our own destiny,” said Kamau Franklin, the South Region director of American Friends Service Committee. “We now have the ability to organize simultaneous marches around the country. All we have to do is use the communication tools we have at hand to change our lives. It’s really up to us to seize the moment.”