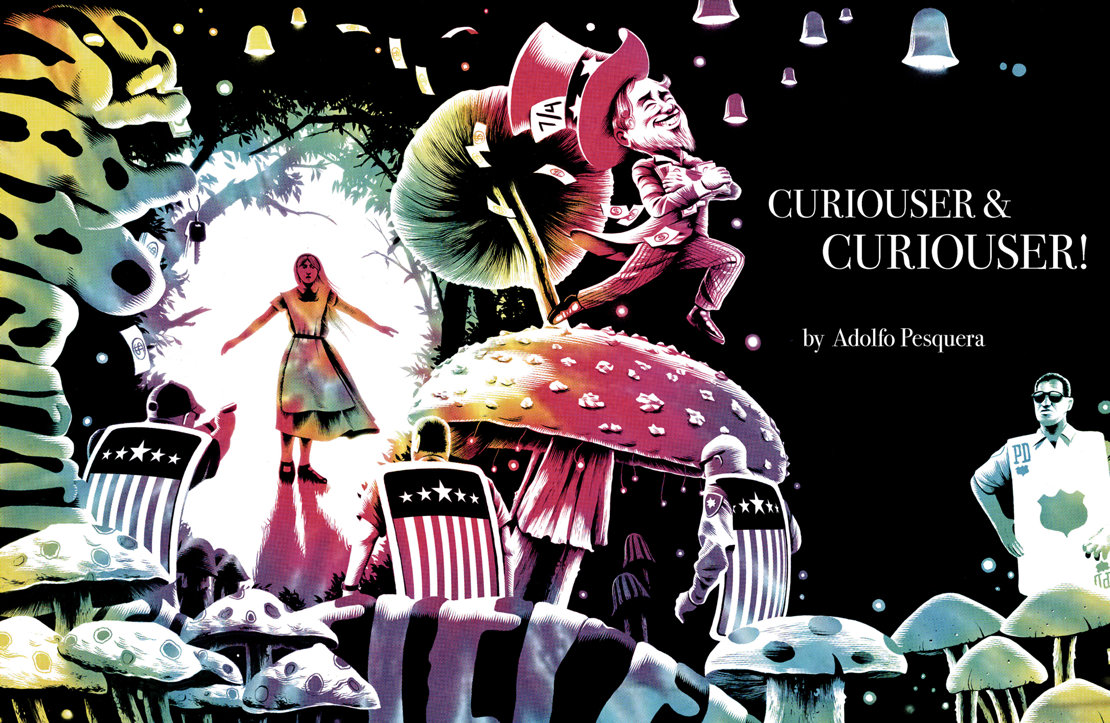

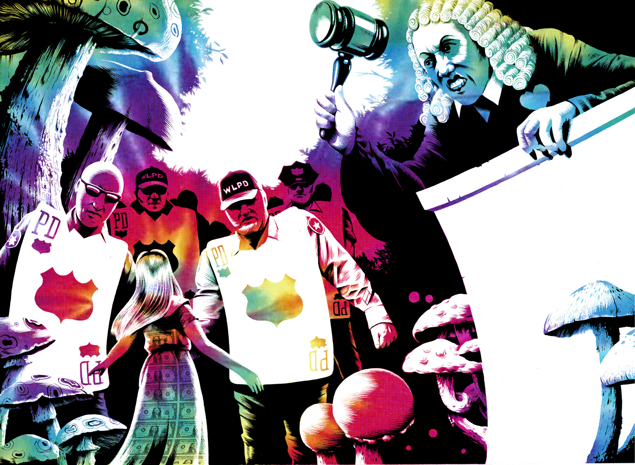

Civil forfeiture empowers law enforcement to seize cash and property alleged to be the proceeds or instrument of a crime, without having to convict or even charge anyone with wrongdoing. In theory, it targets ill-gotten gains. In practice, it enables the state to grab assets fairly indiscriminately and spend them with little accountability. Curious? Come with Alice on a journey down the hole to see how this practice strikes at the heart of some of America’s most cherished principles, like the right to life, liberty and property and the presumption of innocence.

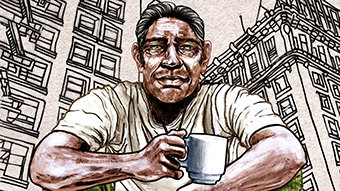

On a snowy afternoon in February 2013, Lorenzo Ayala, a farmer from Mexico, was driving on U.S. 90, America’s longest interstate highway, across Montana. He had traveled alone a little more than 1,000 miles from Palo Alto, California, where his daughter lived, to the Treasure State to buy spare parts for his tractor. The trip wasn’t just about business: Ayala was also there to meet a woman he had been romancing on the Internet.

But the farmer’s plans were cut short when a Montana Highway Patrol trooper pulled him over for driving with an expired out-of-state license plate. Because Ayala reeked of cologne, he fit the profile of a drug courier using perfume to mask the smell of marijuana. But the cologne was intended for his date, according to Ayala’s lawyer, Chris Young. A search of the car revealed no drugs, but the trooper found $16,000 in cash in the trunk.

The officer seized the money, suspecting it was linked to contraband. Although there was nothing illegal in Ayala’s car and no charges were ever brought against him, he never got it back.

Ayala was the victim of civil asset forfeiture, a legal doctrine that allows law enforcement officers to seize any property deemed to be used in or derived from a crime—with or without the owner’s knowledge and without ever having to convict or even charge them.

On its face, asset forfeiture seems reasonable: it’s aimed at targeting ill-gotten gains like the profits of organized crime and drug trafficking. In practice, however, the law enables police to grab private property without the possibility of being sued. Critics say it violates Fifth Amendment protections safeguarding life, liberty and property.

What makes asset forfeiture particularly pernicious is that under the law charges are typically not brought against the owner of property believed to be linked to a crime. Instead, charges are brought against the property itself.

Ayala, for example, was arrested but never prosecuted. Instead, the money seized from him was the “defendant” in an asset forfeiture lawsuit that the government won because Ayala, who didn’t have a U.S. bank account or any credit cards, failed to prove that the money he was carrying was “innocent.” The entire amount, deemed “guilty” at the outset, was forfeit.

Asset forfeiture has resulted in some bizarre lawsuit names, such as United States v. $10,500 in U.S. Currency and United States v. One 2004 Chevrolet Silverado. In one instance, police in Texas seized a gold cross that a woman wore around her neck during a traffic stop. The resulting case: State of Texas v. One Gold Crucifix.

The most common legal standard for asset forfeiture, employed by the federal government and 27 states, is ‘preponderance of the evidence,’ according to the Institute for Justice, an Arlington, Virginia-based law firm engaged in litigation and advocacy on behalf of what it describes as “individuals whose most basic rights are denied by the government.”

The lowest standard used for forfeiture is probable cause—the same criterion used to serve search warrants—used by authorities in 14 states. Only in six states is the government required to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a person is guilty before his or her assets can be seized. Montana and New Mexico are the most recent additions to this list, which includes California, Nebraska, North Carolina and Wisconsin.

Only in six states is the government required to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that someone is guilty of a crime before seizing assets. Civil liberties groups call it “policing for profit” and “legalized theft.”

But even states that employ the highest legal standard can get around it. A practice called equitable sharing enables state and local law enforcement agencies to transfer seized assets to their federal counterparts, who can initiate federal forfeiture actions with less burdensome standards. Then, when assets are successfully forfeited to the federal government, the proceeds are deposited in the Department of Justice Asset Forfeiture Fund which kicks back as much as 80 percent to the state or local agency.

The federal fund was born of the 1984 Comprehensive Crime Control Act. Subsequent changes to the law dramatically expanded what the fund could be used for. As a result, law enforcement agencies developed a direct financial incentive to seize assets—a practice that civil liberties groups call “policing for profit” and “legalized theft.”

According to U.S. Department of Justice statistics cited by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative research and educational institution, the Asset Forfeiture Fund grew from $27 million in 1985 to $1.8 billion in 2011. In 2012, the value of assets seized by the federal government alone stood at $4.3 billion. Meanwhile, equitable sharing payments to states nearly doubled, to about $400 million during an eight-year period ending in 2008.

A 1995 study by former Illinois congressman Henry Hyde and the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, revealed that 80 percent of people subject to asset forfeiture had never been charged with a crime. “Unfortunately, I think I can say that our civil asset forfeiture laws are being used in terribly unjust ways and are depriving innocent citizens of their property with nothing that can be called due process,” Hyde said in 1997 while he was Republican chairman of the House Judiciary Committee.

Two years later, Hyde authored and helped push through Congress the Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Act of 2000, which gives victims of asset forfeiture the right to recoup legal fees from the government if they prevail in court. The law does not, however, require law enforcement agencies to convict property owners before their assets can be forfeited.

The roots of asset forfeiture lie in America’s British colonial past, when officials could legally enter homes or ships and seize anything they believed to be contraband. Although such practices helped spark the American Revolution, it wasn’t long before the U.S. Congress authorized forfeiture as a feature of maritime law. Because the owner of a ship used for piracy or smuggling might be halfway around the globe, well beyond the reach of courts, the pragmatic solution was to bring charges against the ship, show that it was “guilty,” and seize it.

What began as a means to police crimes on the high seas morphed into the so-called Confiscation Acts during the Civil War, which authorized the forfeiture of property belonging to Confederates and their supporters. The Supreme Court upheld those acts against constitutional challenges, spawning “a revolution in forfeiture law that persists to this day,” according to University of Baltimore Law Professor James Maxeiner.

The most controversial aspect of asset forfeiture law is that it amounts to punishing people outside the criminal justice system.

What’s more, there’s little or no oversight on how police departments and government attorneys spend forfeiture funds. In Fulton County, Georgia, which covers most of Atlanta, the district attorney’s office reportedly spent $5,600 in federal forfeiture funds on a Christmas party and $4,800 on a 2010 awards gala, hosted in a historic mansion and featuring goodies like sirloin tip and mini crab cakes in a champagne sauce.

Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard spent $8,200 in state and federal forfeiture funds on a security system for his home. Although DOJ guidelines specify that agencies participating in the federal equitable sharing program must “avoid any appearance of extravagance, waste or impropriety,” Howard has reportedly insisted that he has done nothing wrong, and that he has wide discretion in how he spends equitable sharing funds.

Just how reliant on forfeiture money law enforcement agencies have become is evident in a quote the American Civil Liberties Union collected in connection with a lawsuit it filed in Arizona this July on behalf of a woman whose pickup truck was swiped by the Pinal County Sheriff’s Department. “When the economy tanked and we lost a good part of our budget, we could absolutely not survive without [forfeiture funds],” Chris Radtke, chief of the Sheriff’s Department administrative bureau, told a Tucson TV station in 2013.

The problem with asset forfeiture, reform activists say, isn’t so much how proceeds from the law are spent but where they come from. The Institute for Justice reported in 2011, for example, that the median value for seized property in Georgia was $647. “Evidently, forfeiture mainly targets working-class Georgians, not drug kingpins,” the institute remarked.

Reform activists also find it troubling that the DOJ appears to have only the faintest idea how equitable sharing funds are spent. A compliance team the DOJ set up in 2011 had audited only 11 of the 9,200 participating state and local agencies by the end of the year, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report. Of the 11, only two agencies were in full compliance.

In January 2015, in what U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder described as the “first step in a comprehensive review” of federal civil asset forfeiture practices, federal agencies were ordered to stop accepting property seized by local and state police under the equitable sharing program, unless the assets include firearms, ammunition, explosives, child pornography or other materials impacting public safety.

Although the policy doesn’t affect property seized under joint state and federal operations (and local police forces can still seize assets under state laws), civil liberties groups have praised Holder’s directive as a significant move toward reform.

Indeed, after a quarter century of calls to rein in asset forfeiture laws, some headway is finally being made—thanks in no small part to several journalistic exposés on the law’s misuse.

In August 2013, an 11,000-word article in The New Yorker pushed the issue to the national forefront. Titled “Taken,” it described in infuriating detail a set of alleged asset forfeiture abuses by law enforcement officers in two Texas towns, Shelby and Tenaha, where authorities are facing a class action lawsuit by forfeiture victims.

In Tenaha, population 1,170, a highly decorated former state trooper used “pretextual traffic stops” on out-of-state rental cars to seize assets worth nearly $1.3 million in six months. “In some Texas counties,” the article reported, “nearly 40 percent of police budgets comes from forfeiture.”

In Minnesota, a May 2014 near-unanimous vote in the state legislature led to the passage of a law requiring that police obtain a criminal conviction before seizing personal property. It was the first meaningful asset forfeiture reform undertaken by any state in more than a decade.

In Tenaha, Texas (population 1,170) a state trooper used “pretextual traffic stops” on out-of-state rental cars to seize assets worth nearly $1.3 million—in six months.

At the time, the only other state with a conviction requirement for asset forfeiture was North Carolina. And the reform in Minnesota came only after a series of scandals led to the disbandment in 2009 of the state’s multi-jurisdictional Metro Gang Strike Force, which had been accused of conducting specious raids, illegally seizing property and—in a practice that appears to have become all too typical of many police agencies—using forfeiture funds to pay for trips to Hawaii.

Minnesota’s success last year, combined with the continued media exposure of asset forfeiture practices, set the stage for a slew of new reform bids in 2015. In marked contrast to legislatures in Florida, Texas, Virginia and Colorado, where reform bills failed to make it alive out of committees, the California Assembly considered a bill in July aimed at requiring both police and prosecutors to get a conviction before seizing property. The bill, which passed the state senate in June by a vote of 38-1, also requires law enforcement agencies and government attorneys to keep a smaller percentage of seized assets than is allowed under the federal equitable sharing program.

Two more states that successfully passed asset forfeiture reform bills into law this year are New Mexico and Montana. Both had previously earned a D+ rating on forfeiture standards from the Institute for Justice.

Public opposition to asset forfeiture had been building for several years in New Mexico. “Law enforcement was diverting money to pet causes, property was being taken that seemed unjust to some people,” Brad Cates, a legislative attorney and former director of the DOJ’s Asset Forfeiture Office, told Freedom. “It has, at the very least, the appearance of impropriety if not actual injustice.”

As of July, authorities in New Mexico must obtain a criminal conviction or a guilty plea before seizing property. Further, the law closes a loophole left by Attorney General Holder’s January order, which didn’t address joint state and federal forfeitures. Local police in New Mexico may no longer transfer seized assets to federal law enforcement agencies as a way of circumventing the stronger state protections.

Montana, too, now requires a criminal conviction as a prerequisite for seizing assets, according to a new law in that state that also took effect this summer and requires police to present “clear and convincing evidence” that seized property is linked to criminal activity. The law also offers owners of seized property a pretrial process by which they can contest forfeiture actions.

Reformists preparing bills in other states are hoping to duplicate the success in Minnesota, Montana and New Mexico.

“We think folks that are targeted are generally low-income folks who are not going to be able to afford the legal cost to get their property back,” says Jameson Taylor, vice president for policy at the Mississippi Center for Public Policy, a conservative think tank that maintains close ties with reform-minded groups in New Mexico and is eagerly anticipating the 2016 legislative session.

“This isn’t to say that all of our local police officers are doing something wrong,” Taylor adds. “But in many cases we don’t know what they’re doing.”

Asset forfeiture has resulted in some bizarre lawsuit names, like:

United States v. $10,500 in U.S. Currency

United States v. One 2004 Chevrolet Silverado

State of Texas v.

One Gold Crucifix